Become KENYAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC KENYAN LIVING

From its earliest known settlements over 5,000 years ago to its independence in 1963, Kenya has played a key role in the history of East Africa. Situated at the crossroads of ancient trade routes, Kenya’s cultural heritage reflects influences from indigenous communities, Arab traders, European colonial powers, and Indian laborers, all of whom have contributed to the nation’s diverse identity. Known for its breathtaking savannas, Great Rift Valley landscapes, and pristine coastline, Kenya offers a captivating journey through its deep-rooted traditions and modern transformation.

After gaining independence from British colonial rule, Kenya embarked on a path of economic growth, political evolution, and technological advancement. Today, it is one of Africa’s leading economies and a hub for innovation, trade, and tourism. Nairobi, often called “Silicon Savannah”, is a leader in digital entrepreneurship and mobile banking, while the country's national parks and wildlife reserves attract millions of visitors each year. Kenya’s rich cultural diversity, with over 40 ethnic groups, contributes to its vibrant traditions, music, arts, and cuisine.

We have created a selection of cultural insights to help you truly connect with Kenyans. By learning Swahili words and phrases that go beyond textbooks or phone app courses, you’ll uncover the rich essence of this extraordinary country and feel at home in its distinctive cultural fabric.

Speak and think like a real Kenyan!

BOMA

A boma is a traditional homestead structure that has played a central role in rural Kenyan life for generations. The term boma (homestead or enclosure) describes a compound that typically includes living houses, livestock enclosures, storage areas, and shared outdoor spaces. It functions not only as a physical dwelling but also as a social and economic unit that reflects family organization and cultural values.

The layout of a boma is closely linked to household structure and security needs. Homes are usually arranged around a central open area, with fencing made from wood, thorn bushes, or other locally available materials. This enclosure provides protection for people and animals, particularly livestock such as cattle and goats, known as mifugo (livestock). The positioning of houses and animal pens follows practical considerations related to safety, hygiene, and ease of daily work.

Construction methods for a boma rely heavily on local resources and community labor. Walls are often built using mud mixed with grass, while roofs may be thatched with dry vegetation or constructed from more durable materials as they become available. Building a homestead traditionally involves collective effort, referred to as kazi ya pamoja (communal work), reinforcing cooperation and mutual support within extended families and neighborhoods. These practices reduce costs and strengthen social ties.

The boma also serves as a center of economic activity. Food preparation, storage of harvests, and small-scale craft production commonly take place within the compound. Agricultural tools such as the jembe (hand hoe) and household utensils are stored and maintained there. Livestock management, including milking and feeding, is integrated into daily routines, making the homestead an essential hub of subsistence production.

Social and cultural life is deeply embedded in the boma. Important family events such as weddings, naming ceremonies, and meetings of elders often occur within the homestead space. Elders, known as wazee (elders), traditionally use the boma as a setting for resolving disputes, passing on knowledge, and teaching younger generations about customs and responsibilities. Oral history, moral instruction, and practical skills are commonly transmitted in this environment.

Over time, the structure and function of the boma have evolved. Modern materials such as corrugated metal roofing and permanent walls are increasingly common, and some activities have shifted outside the homestead due to schooling and wage labor.

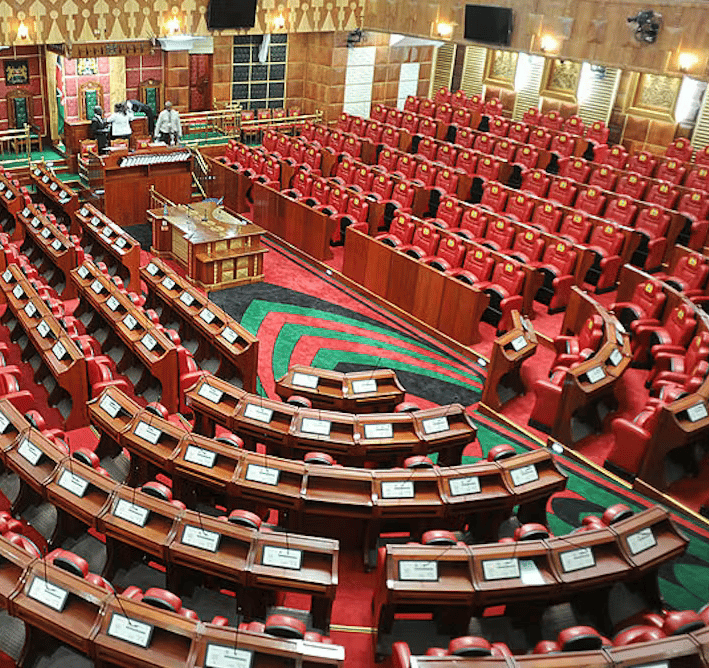

BUNGE

Bunge is the national parliamentary institution of Kenya and forms the core of the country’s legislative authority. The term bunge (parliament) refers to the body responsible for debating, amending, and passing laws, as well as overseeing the executive branch of government. Its structure and functions are defined by the Constitution of Kenya and reflect both historical developments and modern democratic principles.

The origins of the bunge can be traced to the colonial period, when limited legislative councils were established under British administration. These early bodies largely excluded African representation and primarily served colonial interests. Following independence in 1963, the parliamentary system was restructured to reflect national sovereignty and broader political participation. Over time, constitutional reforms expanded representation and clarified the role of parliament within the system of checks and balances.

Today, the bunge consists of two chambers: the National Assembly and the Senate. Members of the National Assembly are elected to represent constituencies and special interest groups, while the Senate represents counties and safeguards their interests at the national level. Parliamentary sessions, known as vikao (sessions), provide a formal setting for lawmaking, debate, and committee work. These sessions are governed by procedural rules designed to ensure order, transparency, and accountability.

One of the primary functions of the bunge is legislation. Proposed laws, referred to as miswada (bills), are introduced, debated, and either approved or rejected through a defined legislative process. Committees play a key role in scrutinizing these bills, consulting experts, and gathering public input. This process allows parliament to shape national policy in areas such as education, health, finance, and security.

Oversight of the executive branch is another central responsibility. Through mechanisms such as parliamentary questions, committee investigations, and approval of budgets, the bunge holds government ministries and officials accountable for their actions. The national budget, known as bajeti (budget), must be debated and approved by parliament, giving elected representatives influence over public spending and development priorities.

Public participation has become an increasingly important aspect of parliamentary work. Citizens, civil society organizations, and professional groups are invited to submit views on proposed legislation and policy matters. This engagement reflects constitutional requirements for inclusivity and transparency, strengthening the link between elected representatives and the public they serve.

CHAMA

A chama is a widely practiced community-based savings and investment system that plays an important role in Kenya’s social and economic life. The term chama (group or association) describes a voluntary collective in which members contribute money or resources on a regular basis for mutual financial benefit. Chamas exist across urban and rural settings and are used by people from diverse economic and social backgrounds.

The basic structure of a chama is built around regular contributions, known as michango (contributions). Members agree on a fixed amount to be paid weekly or monthly, and these funds are pooled together. Depending on the group’s rules, the money may be distributed to members in rotation, saved for long-term goals, or invested in joint projects. Clear internal regulations help maintain trust and accountability within the group.

Chamas often operate through scheduled meetings, referred to as vikao (meetings), where members collect contributions, review records, and make decisions. These gatherings also serve a social function, reinforcing relationships and shared responsibility. Leadership roles such as chairperson, treasurer, and secretary are commonly assigned to ensure proper management of funds and documentation.

One of the key purposes of a chama is financial inclusion. For many members, especially those without access to formal banking services, chamas provide a reliable way to save money and access credit. Members may take loans from the pooled funds, known as mikopo (loans), usually at lower interest rates than those offered by commercial lenders. Repayment terms are agreed internally, making the system flexible and responsive to members’ needs.

Beyond savings and lending, many chamas engage in collective investment. Funds may be used to purchase land, support small businesses, or invest in income-generating activities such as agriculture or rental housing. These ventures allow members to build assets and share risks. The success of such projects depends on careful planning, transparency, and strong group cohesion.

Chamas also play an important role in social support. Many groups provide financial assistance during life events such as weddings, medical emergencies, or funerals. This support system, often described as msaada wa kijamii (social support), helps members manage unexpected expenses and reinforces solidarity within the group. Participation in a chama is therefore both an economic strategy and a form of social insurance.

In recent years, chamas have adapted to technological and regulatory changes. Some groups now use mobile money platforms, known as pesa ya simu (mobile money), to collect contributions and track transactions more efficiently. Others register formally to access larger investment opportunities or partner with financial institutions. Despite these changes, the core principles of trust, cooperation, and shared responsibility remain central.

Chamas continue to be a defining feature of Kenya’s informal financial sector. Their flexibility, cultural acceptance, and effectiveness have allowed them to thrive alongside formal banking systems. As Kenya’s economy evolves, chamas remain a practical and culturally embedded mechanism for saving, investing, and strengthening community ties.

CHAPATI

Chapati is a widely consumed flatbread that has become an integral part of everyday meals and social gatherings across the country. The expression chapati ya Kenya (Kenyan-style chapati) refers to a locally adapted version of the flatbread that differs in texture, preparation, and social use from similar foods found elsewhere. It is valued for its versatility, affordability, and association with hospitality and celebration.

Kenyan chapati is typically prepared using wheat flour, water, salt, and cooking oil. The dough is kneaded thoroughly to develop elasticity, rested to improve texture, and then rolled into thin layers before being cooked on a flat pan. The cooking surface, known as a sufuria (cooking pan), allows the bread to brown evenly while remaining soft inside. The use of oil between layers gives Kenyan chapati its characteristic flaky structure, distinguishing it from simpler flatbreads.

Preparation of chapati ya Kenya is often labor-intensive and time-consuming, which contributes to its cultural significance. Because of this effort, chapati is commonly associated with special occasions rather than everyday meals. It frequently appears during family gatherings, religious celebrations, and public holidays. Serving chapati is widely seen as a sign of generosity and care toward guests, reflecting values of hospitality and respect.

Chapati is usually eaten alongside savory dishes such as legumes, vegetables, or meat stews. One common accompaniment is maharagwe (beans), which provides protein and complements the bread’s texture. In many households, chapati is also paired with mboga (vegetables), creating a balanced meal using locally available ingredients. The bread’s neutral flavor allows it to absorb sauces and gravies, making it adaptable to a wide range of dishes.

The preparation and sharing of chapati often involve multiple family members, reinforcing social bonds. Knowledge of how to make good chapati is commonly passed down through observation and practice rather than formal instruction. Older family members, especially women, play a central role in teaching younger generations techniques related to kneading, rolling, and cooking. This transfer of skills contributes to the preservation of culinary traditions within households.

In urban areas, chapati ya Kenya is also widely sold by informal vendors and small eateries. These establishments produce chapati in large quantities to meet daily demand, especially during lunch and evening hours. The bread’s popularity in urban settings reflects its role as both a comfort food and a practical meal option for people with limited time and resources.

HARAMBEE

Harambee is a foundational social and political concept in Kenya that expresses collective action, mutual assistance, and shared responsibility. The word harambee (pulling together) became nationally prominent during the early years of independence and has since remained a core value shaping community organization and public life. It captures the idea that social and economic progress is best achieved through cooperation rather than individual effort alone.

Historically, practices aligned with harambee existed long before independence. Kenyan communities relied on collective labor for farming, house construction, and social ceremonies. These cooperative efforts were organized around kinship networks, age groups, and neighborhood ties. After independence, the concept was formalized and promoted as a national philosophy to mobilize resources for development at a time when state capacity and financial resources were limited.

Harambee activities typically involve communities coming together to raise funds, contribute labor, or provide materials for shared goals. Common initiatives include building schools, health facilities, water projects, and places of worship. Contributions may be financial, referred to as michango (contributions), or take the form of labor and skills. These activities reinforce local ownership of development projects and reduce reliance on external support.

The concept also became closely linked to political leadership and state policy. National leaders encouraged harambee as a means of fostering unity and accelerating development. Public fundraising events, often attended by political figures, became common. While these events helped finance infrastructure and social services, they also raised questions about equity, accountability, and the influence of politics in community initiatives.

Harambee plays an important social role beyond development projects. It functions as a system of mutual support during major life events such as weddings, funerals, and medical emergencies. Community members contribute resources to assist affected families, reinforcing solidarity and shared responsibility. This social dimension is often described as msaada wa jamii (community support) and remains vital, particularly in contexts where formal social welfare systems are limited.

Over time, the practice of harambee has evolved. Economic changes, urbanization, and increased access to formal financial institutions have altered how communities mobilize resources. In urban settings, harambee initiatives may be organized through workplaces, religious groups, or social associations rather than extended families. Digital platforms and mobile money have also transformed fundraising methods, increasing efficiency and transparency.

Despite its positive role, harambee has faced criticism. Concerns have been raised about unequal burdens on poorer communities, pressure to contribute beyond one’s means, and misuse of funds in some cases. In response, greater emphasis has been placed on accountability, clear rules, and voluntary participation to preserve the integrity of the practice.

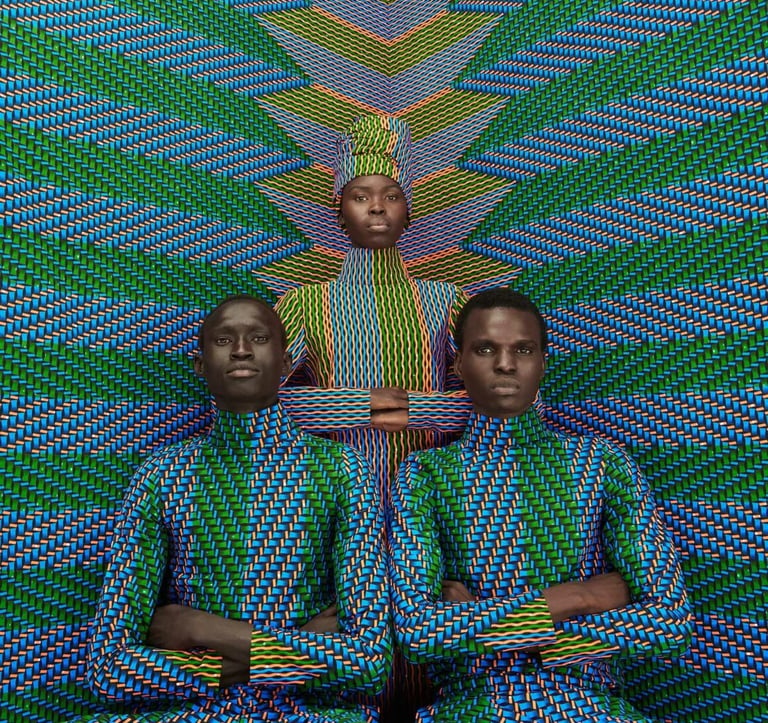

KHANGA

Khanga is a widely used textile in Kenya that functions as clothing, a communication medium, and a household item. The word khanga (printed cotton cloth) refers to a rectangular piece of fabric characterized by bold patterns, a decorative border, and a Swahili inscription. While similar textiles exist elsewhere, khanga has a distinct role in Kenyan social life due to its everyday use and symbolic meanings.

Khanga is commonly worn by women as a wrap, dress, or head covering. Its practicality allows it to be adapted to different settings, from domestic work to public gatherings. The cloth is valued for comfort, durability, and ease of use. In many households, it is also used for carrying children, covering furniture, or performing household tasks, demonstrating its multifunctional nature.

A defining feature of khanga is the presence of a written message, known as ujumbe (message). These inscriptions are typically printed along the lower edge and convey statements related to advice, emotion, dignity, or social commentary. The messages allow wearers to communicate indirectly, particularly in situations where direct speech may be socially sensitive. This form of expression aligns with cultural norms that emphasize discretion and respect.

Khanga plays an important role in social exchange. It is commonly given as a gift during significant life events such as weddings, childbirth, or periods of mourning. In these contexts, the selected message carries meaning beyond the fabric itself. Giving a khanga is understood as an act of ukarimu (generosity) and social acknowledgment, reinforcing relationships and obligations.

Production and trade of khanga have long been linked to regional commerce. Historically, these textiles circulated through trade networks and became embedded in local economies. Today, khanga are produced for mass markets and sold widely in shops and open-air markets. Their affordability and accessibility contribute to their continued popularity across economic groups.

Khanga also serves as a marker of identity and status. Choices of color, pattern, and message can signal age, marital status, or personal values. Certain messages become popular during specific periods, reflecting social trends or shared concerns. In this way, khanga responds dynamically to changing social contexts while maintaining a recognizable form.

Language is central to the cultural significance of khanga. The use of Swahili ensures that messages are broadly understood across Kenya’s diverse linguistic landscape. This linguistic accessibility allows the cloth to function as a unifying cultural object. Messages often draw on shared values such as patience, resilience, and self-respect.

In contemporary Kenya, khanga continues to evolve. Designers experiment with new color schemes and modern themes while retaining traditional elements. The cloth appears in fashion, art, and public campaigns, demonstrating its adaptability.

MAGADI

Magadi is a historically important mineral resource in Kenya that has played a role in industry, trade, and traditional practices. The term magadi (soda ash or trona) refers to a naturally occurring mineral rich in sodium carbonate. It has been used for generations in local contexts and later became a significant industrial raw material within Kenya’s extractive economy.

Traditionally, magadi was known and utilized by local communities for practical domestic purposes. It was used in food preparation to soften vegetables and reduce cooking time, a process known as kupika kwa magadi (cooking with soda ash). Small quantities were also applied in soap-making and cleaning, reflecting early chemical knowledge embedded in everyday practices. These uses demonstrate how communities identified and exploited natural resources long before industrial extraction.

Magadi gained wider economic importance with the development of large-scale extraction. Soda ash derived from magadi is used in the manufacture of glass, detergents, chemicals, and water treatment products. Its industrial processing transformed it into a valuable export commodity and integrated Kenya into global supply chains. This shift marked a transition from localized use to commercial exploitation.

Extraction and processing of magadi require specialized infrastructure and technical expertise. The mineral is collected, refined, and transported for industrial use. These activities generate employment and contribute to national revenue. Workers involved in extraction and processing depend on ajira ya viwandani (industrial employment), linking mineral resources to livelihoods and regional development.

Magadi also has environmental implications. Mining activities affect surrounding ecosystems and water systems, requiring careful management. Environmental regulation and monitoring aim to balance economic benefits with sustainability. Concepts such as uhifadhi wa mazingira (environmental conservation) are increasingly emphasized in discussions around mineral extraction to mitigate negative impacts.

In addition to industrial use, magadi continues to hold cultural relevance. Knowledge of its traditional applications is preserved in oral history and household practices, particularly among older generations. This continuity illustrates how industrialization does not entirely replace indigenous knowledge but exists alongside it.

Public awareness of magadi has expanded through education and media, highlighting its role in national development. Discussions about resource management, value addition, and local benefit-sharing have become more prominent. These debates reflect broader concerns about equitable use of natural resources and long-term economic planning.

Technological advances have improved extraction efficiency and product quality. Investment in modern processing techniques aims to enhance competitiveness while reducing environmental impact. Such improvements are part of wider efforts to modernize Kenya’s industrial sector and diversify exports.

MAU MAU

Mau Mau refers to the anti-colonial liberation movement that emerged in Kenya during the 1940s and 1950s in response to British colonial rule. The term mau mau (anti-colonial resistance movement) is used to describe a complex political, social, and military struggle centered primarily among the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru communities. The movement became a defining episode in Kenya’s path toward independence.

The origins of Mau Mau are closely linked to land dispossession, forced labor, and political exclusion under colonial administration. Large areas of fertile land had been taken from African communities, creating widespread grievances. These injustices were articulated through nationalist activism and later through organized resistance. Participants committed themselves to the cause through kiapo (oath), a ritual that symbolized unity, secrecy, and loyalty to the struggle.

Mau Mau organization relied on both rural and urban networks. Fighters operating in forested areas engaged in guerrilla warfare, while supporters in towns and villages provided food, information, and supplies. The forest fighters were commonly referred to as wapiganaji wa msituni (forest fighters), and their operations depended on mobility, local knowledge, and community support. This structure allowed the movement to sustain resistance despite limited resources.

The colonial government responded with a state of emergency declared in 1952. Security forces conducted mass arrests, detentions, and relocations aimed at dismantling the movement. Large numbers of people were confined in detention camps and villages under surveillance. These measures had profound social effects, disrupting families and communities while intensifying political awareness and resistance.

Despite military suppression, Mau Mau had lasting political impact. The conflict exposed the contradictions of colonial rule and accelerated constitutional reforms. International attention to the emergency and its human cost increased pressure for political change. Former detainees and sympathizers later became active participants in nationalist politics, contributing to the emergence of independent leadership.

After independence, Mau Mau memory remained contested. For many years, official narratives marginalized the movement, emphasizing reconciliation and national unity. Over time, public recognition expanded, acknowledging Mau Mau as a legitimate freedom struggle. The movement is now widely understood as a critical component of Kenya’s liberation history.

Mau Mau also shaped national identity and historical consciousness. It became a symbol of resistance, sacrifice, and determination in the face of oppression. Discussions of the movement highlight themes of land, justice, and political inclusion that continue to influence public debate. The legacy of Mau Mau is often invoked in conversations about rights, governance, and historical accountability.

In contemporary Kenya, Mau Mau is commemorated through education, memorials, and public discourse. Survivors and descendants continue to seek recognition and redress for historical injustices. The movement’s history is studied to understand both the costs of colonialism and the foundations of independence.

MATATU

Matatu is a defining feature of Kenya’s urban and interurban transport system and a major component of everyday mobility. The word matatu (public minibus) refers to privately owned vehicles that operate on fixed or semi-fixed routes, carrying passengers for a fare. This system emerged to fill gaps left by formal public transport and has since become essential to economic activity and daily life.

The matatu sector developed rapidly after independence as urban populations expanded and demand for affordable transport increased. Entrepreneurs converted vans and minibuses into passenger vehicles, creating a flexible system responsive to changing routes and schedules. Today, matatus connect residential areas to workplaces, schools, markets, and transport hubs, making them a primary means of movement for millions of people.

Operation of matatus relies on a distinct labor structure. Each vehicle is typically run by a driver and a fare collector known as a kondakta (fare conductor). The conductor manages passenger boarding, fare collection, and route coordination. This division of roles allows for quick turnover and adaptability in congested urban environments, where communication and timing are critical.

Routes followed by matatus are known as njia (routes) and are regulated through licensing and local agreements. Vehicles queue at designated stops and terminals, commonly called vituo (stops), where passengers board. Although routes are defined, flexibility allows drivers to respond to traffic conditions and passenger demand, distinguishing matatus from rigid mass transit systems.

The matatu industry is also an important source of employment and income. Beyond drivers and conductors, it supports mechanics, vehicle owners, cleaners, and informal vendors operating at stops. Revenue from fares contributes to kipato cha mijini (urban income) and sustains a wide network of livelihoods linked to transport services.

Cultural expression is a notable feature of matatu culture. Many vehicles are decorated with colorful artwork, slogans, and music systems. This visual and auditory style reflects youth culture, popular music, and social commentary. While decoration attracts passengers and expresses identity, it has also prompted regulation aimed at balancing creativity with safety and public order.

Regulation of the matatu sector has increased over time to address safety and organization. Authorities enforce standards related to vehicle condition, driver conduct, and passenger limits. Compliance with sheria za usafiri (transport regulations) aims to reduce accidents and improve reliability, although enforcement remains a challenge due to the sector’s size and informality.

Matatus play a critical role during peak hours, facilitating commuting in densely populated cities. Despite issues such as congestion and occasional safety concerns, their frequency and reach make them indispensable. Passengers value their availability, affordability, and ability to access areas not served by larger buses.

In recent years, technology has begun to influence matatu operations. Mobile payment systems, GPS tracking, and digital route mapping are being introduced to improve efficiency and transparency. These innovations reflect efforts to modernize the sector while retaining its flexibility.

MORAN

Moran refers to a recognized age-set identity associated with warriorhood among certain Kenyan pastoral communities and has become a nationally recognized cultural concept. The word moran (age-set warrior) describes young men who have undergone initiation and entered a distinct social stage marked by discipline, responsibility, and communal service. While rooted in specific cultural systems, the concept is widely understood across Kenya as a symbol of transition to adulthood and social duty.

The moran stage follows formal initiation rites that mark entry into adulthood. After initiation, individuals are grouped into age-sets that progress through life together. Membership in an age-set creates lifelong bonds and shared obligations. During this period, morans are expected to display physical endurance, courage, and adherence to community norms. These expectations are reinforced through training, mentorship, and collective living arrangements.

Traditionally, morans were responsible for protecting livestock, territory, and community members. Their role included guarding herds, responding to external threats, and maintaining security in challenging environments. This responsibility required deep knowledge of the landscape, survival skills, and coordination. The emphasis on protection reflects the centrality of livestock and land to pastoral livelihoods.

Social conduct is a key component of moran identity. Morans are expected to uphold nidhamu (discipline) and respect community authority, particularly elders. Although they occupy a visible and sometimes assertive position, their actions are regulated by customary rules. Elders provide guidance and oversight, ensuring that strength and bravery are balanced with restraint and responsibility.

The moran stage is temporary and transitional. After a defined period, members move on to the next age-set, assuming roles associated with greater social authority, such as household leadership and decision-making. This progression illustrates a structured life course in which responsibilities change over time. The system promotes continuity by preparing younger generations for future leadership.

Cultural expression associated with moran identity includes distinctive dress, adornment, and bodily presentation. Hairstyles, ornaments, and attire signal age-set membership and social status. These visual markers communicate identity within and beyond the community, reinforcing recognition and cohesion. Songs, dances, and public performances may also accompany age-set events, strengthening shared identity.

In contemporary Kenya, the concept of moran has evolved. While traditional warrior roles have diminished due to changes in security, governance, and livelihoods, the identity remains culturally significant. Morans may now symbolize youth, strength, and cultural heritage rather than active combat roles. Cultural festivals, education, and media often reference moran identity to highlight tradition and continuity.

Public understanding of moran has expanded beyond its original context. The term is used nationally to evoke ideas of courage, readiness, and cultural pride. However, there is also ongoing discussion about how traditional age-set roles adapt to modern education, employment, and legal systems. Balancing cultural preservation with changing social realities remains an important theme.

Overall, moran represents a structured approach to youth development and social responsibility within Kenyan society. It emphasizes discipline, service, and progression through life stages. As both a lived experience and a cultural symbol, moran continues to inform discussions about identity, tradition, and the role of youth in Kenya’s past and present.

MSHIKAKI

Mshikaki is a popular Kenyan food that refers to skewered meat grilled over an open fire and widely consumed in both urban and rural settings. The word mshikaki (skewered grilled meat) describes small pieces of meat, most commonly beef or goat, threaded onto sticks and cooked over charcoal or firewood. It is valued for its simplicity, affordability, and strong association with social eating.

Preparation of mshikaki begins with cutting meat into small, even cubes. The pieces may be lightly seasoned with salt and spices before being skewered. Cooking is done slowly over open heat, requiring careful turning to ensure even roasting. This method enhances flavor while keeping the meat tender. The process reflects practical cooking knowledge associated with kupika kwa moto wa wazi (open-fire cooking), a technique common in many Kenyan food practices.

Mshikaki is closely linked to informal food spaces. It is commonly sold at roadside stalls, markets, and evening food points where people gather after work. These locations provide accessible meals at low cost, making mshikaki popular among workers, students, and travelers. Eating skewered meat while standing or socializing reflects the casual and communal nature of the experience.

Social interaction is central to mshikaki consumption. People often eat it in groups, sharing conversation while waiting for meat to cook. This setting supports maingiliano ya kijamii (social interaction), turning food consumption into a shared activity rather than a private one. The open preparation allows customers to observe cooking, reinforcing trust and engagement.

Mshikaki is also associated with celebrations and informal gatherings. It may be prepared during family events, community meetings, or leisure occasions. In these contexts, skewered meat complements other dishes and reinforces hospitality. Serving mshikaki demonstrates effort and generosity without requiring elaborate preparation.

Economically, mshikaki supports small-scale entrepreneurship. Vendors require minimal equipment and investment, relying on grills, skewers, and steady customer flow. This activity contributes to biashara ndogo (small business) and provides livelihoods for many individuals. The flexibility of the trade allows vendors to operate seasonally or alongside other work.

Cultural significance of mshikaki lies in its accessibility and adaptability. While ingredients and seasoning may vary, the basic method remains consistent. This consistency makes mshikaki recognizable across regions and social groups. It serves as a shared culinary reference point, bridging differences in background and income.

Health and safety considerations influence contemporary mshikaki preparation. Urban authorities may regulate cooking spaces to ensure hygiene and reduce smoke exposure. Vendors adapt by improving cleanliness and fuel efficiency while maintaining traditional methods. These adjustments reflect ongoing negotiation between tradition and regulation.

In modern Kenya, mshikaki continues to thrive despite the availability of fast food alternatives. Its appeal lies in freshness, affordability, and social atmosphere. For many people, it represents everyday enjoyment rather than special occasion dining.

Overall, mshikaki is more than a food item. It is a social practice, an economic activity, and a culinary tradition embedded in Kenyan daily life. Through open-fire cooking, informal exchange, and shared enjoyment, mshikaki remains a defining element of Kenya’s food culture.

MUKIMO

Mukimo is a traditional Kenyan dish that reflects agricultural practice, household economy, and regional food culture. The word mukimo (mashed mixed dish) refers to a meal prepared by mashing together boiled tubers and vegetables, commonly including potatoes, green peas, maize, or leafy greens. It is valued for its nutritional balance, simplicity, and strong association with home cooking.

Mukimo preparation begins with boiling the main ingredients until soft. The components are then mashed together to form a thick, cohesive mixture. This method allows different foods to be combined efficiently, maximizing use of available produce. The technique, known as kupika kwa kuchanganya (mix-and-mash cooking), reflects practical adaptation to seasonal harvests and household resources.

The dish is closely linked to smallholder farming. Ingredients used in mukimo are typically grown in family plots, making the meal an extension of ukulima wa nyumbani (household farming). Because the components are locally produced and affordable, mukimo supports food security and reduces reliance on purchased foods. It is especially common during periods when fresh produce is abundant.

Mukimo is nutritionally significant. The combination of carbohydrates from tubers and proteins from legumes creates a balanced meal. Leafy greens add vitamins and minerals, improving dietary quality. This composition supports lishe bora (balanced nutrition), particularly in rural households where access to diverse foods may be limited.

Socially, mukimo is associated with family meals and communal eating. It is often prepared in large quantities and shared among household members. Serving mukimo reflects care and provision, especially during gatherings or when hosting visitors. Although simple, the dish is considered filling and satisfying, reinforcing its role in everyday sustenance.

Mukimo is commonly eaten with accompaniments such as meat, stew, or vegetables. These additions depend on availability and occasion. In many cases, the dish stands alone as a complete meal, highlighting its versatility. The ability to adapt mukimo to different contexts contributes to its enduring popularity.

Knowledge of how to prepare mukimo is transmitted informally. Children learn by observing and assisting elders in the kitchen. Decisions about ingredient proportions and texture are based on experience rather than fixed recipes. This learning process supports urithi wa upishi (culinary heritage), ensuring continuity across generations.

Urbanization has influenced how mukimo is consumed. While still common in rural areas, the dish is also prepared in towns and cities, sometimes using alternative ingredients to suit availability. Restaurants and eateries may serve mukimo as a traditional option, reinforcing its cultural significance beyond the household.

In contemporary discussions about diet and culture, mukimo is often highlighted as an example of traditional food that aligns with modern nutritional recommendations. Its reliance on plant-based ingredients and minimal processing makes it relevant in conversations about healthy eating and sustainability.

Overall, mukimo represents the close relationship between agriculture, nutrition, and culture in Kenya. It demonstrates how simple cooking methods transform locally grown foods into sustaining meals. Through everyday preparation and shared consumption, mukimo remains a meaningful element of Kenyan culinary identity and household life.

MZEE

Mzee is a respected social title in Kenya used to refer to an elder and signifies authority, wisdom, and moral standing within society. The word mzee (elder) is applied not only on the basis of age but also in recognition of experience, responsibility, and contribution to the community. The concept plays a central role in social organization, decision-making, and the transmission of values.

In many Kenyan communities, the status of mzee is earned over time through life experience, family leadership, and adherence to social norms. Elders are expected to demonstrate busara (wisdom) and sound judgment, particularly in matters affecting families and communities. Their opinions carry weight in discussions because they are seen as custodians of collective memory and cultural knowledge.

The mzee occupies an important role in family life. Elders guide younger members on issues such as marriage, inheritance, and conflict resolution. They mediate disputes within households and extended families, drawing on precedent and custom rather than written rules. This mediation process supports amani ya familia (family harmony) and helps maintain social stability without reliance on formal institutions.

At the community level, wazee often participate in councils or informal assemblies that address shared concerns. These gatherings provide a forum for deliberation and consensus-building. The authority of elders in such settings is grounded in trust and recognition rather than coercive power. Respect for elder decisions reflects the value placed on continuity and collective responsibility.

Cultural transmission is a key function of the mzee. Elders pass down oral history, customs, and moral lessons through storytelling and advice. This role supports urithishaji wa tamaduni (cultural transmission), ensuring that knowledge and identity are preserved across generations. Through everyday interaction, elders shape behavior and reinforce social expectations.

The concept of mzee also extends into public and political life. Leaders may be referred to as mzee as a sign of respect, regardless of their actual age. This usage emphasizes dignity and authority rather than chronology. It reflects a broader cultural tendency to associate leadership with maturity and responsibility.

Social expectations of a mzee include restraint, fairness, and service. Elders are expected to act as role models, avoiding behavior that would undermine their credibility. Failure to meet these expectations can lead to loss of respect, demonstrating that elder status carries obligations as well as privilege.

Modernization has influenced perceptions of mzeehood. Urbanization, formal education, and changing family structures have altered intergenerational relationships. Younger people may rely less on elders for economic support or decision-making. Despite this, respect for elders remains a strong social norm, even as roles evolve.

In contemporary Kenya, issues such as elder care and social protection have gained attention. As life expectancy increases and traditional support systems change, ensuring dignity and wellbeing in old age has become a policy concern. This reflects recognition of the ongoing value of elders within society.

Overall, mzee represents more than age. It embodies wisdom, authority, and continuity in Kenyan life. Through guidance, mediation, and cultural transmission, elders contribute to social cohesion and moral order. Even as social conditions change, the concept of mzee remains a foundational element of Kenya’s social fabric.

NGOMA

Ngoma is a broad cultural concept in Kenya that refers to traditional dance, drumming, and the integrated performance practices that accompany ceremonies and communal events. The word ngoma (traditional dance and drumming) encompasses music, movement, rhythm, costume, and social meaning, functioning as a central medium for expression, communication, and collective identity.

Ngoma performances are closely tied to life-cycle events and communal occasions. Birth celebrations, initiations, weddings, harvests, and rites of passage are commonly marked by dance and drum ensembles. These performances structure time and meaning, signaling transitions and affirming shared values. Participation is often collective, with performers and audience interacting through call-and-response, clapping, and movement, reinforcing ushiriki wa jamii (community participation).

Drumming is foundational to ngoma. Drums set tempo, cue transitions, and communicate signals understood by participants. Rhythms vary by context and purpose, conveying emotions such as joy, solemnity, or readiness. Skilled drummers coordinate patterns that guide dancers’ movements, demonstrating ufundi wa midundo (rhythmic craftsmanship). The interdependence of drum and dance underscores coordination and mutual awareness.

Dance movements in ngoma are purposeful and symbolic. Gestures, footwork, and formations may represent social roles, historical narratives, or moral lessons. Performers learn sequences through observation and practice rather than notation, embedding knowledge in the body. This embodied learning supports urithishaji wa maarifa (knowledge transmission) across generations.

Ngoma also serves communicative and regulatory functions. Performances can comment on social issues, praise individuals, or critique behavior in socially acceptable ways. Songs and movements may convey advice or warnings, allowing communities to address concerns without direct confrontation. This role aligns with norms of heshima (respect) and indirect communication.

Costume and adornment contribute to ngoma’s meaning. Attire, body decoration, and accessories are selected to match the occasion and identity of performers. Visual elements enhance recognition and reinforce belonging, linking performance to lineage, age-set, or communal role. Preparation for performance is itself a social activity that builds cohesion.

Urbanization and media have expanded ngoma’s visibility and forms. While traditional contexts remain important, performances now appear on stages, in schools, and at public festivals. Choreography may be adapted for wider audiences while retaining core elements. This adaptation reflects uendelevu wa tamaduni (cultural continuity) amid change.

Ngoma is also integral to education and heritage preservation. Schools and cultural organizations use performance to teach history, language, and values. Participation builds confidence, coordination, and appreciation of diversity. Through practice, learners engage with culture as lived experience rather than abstract content.

Economically, ngoma supports livelihoods through performance, instruction, and event organization. Groups may be invited to perform at ceremonies and festivals, generating income while sustaining tradition. This activity links culture to uchumi wa ubunifu (creative economy).

In contemporary Kenya, ngoma remains a dynamic expression of identity. It bridges past and present, ritual and entertainment, instruction and celebration. By integrating music, movement, and community, ngoma continues to anchor social life and articulate shared meaning.

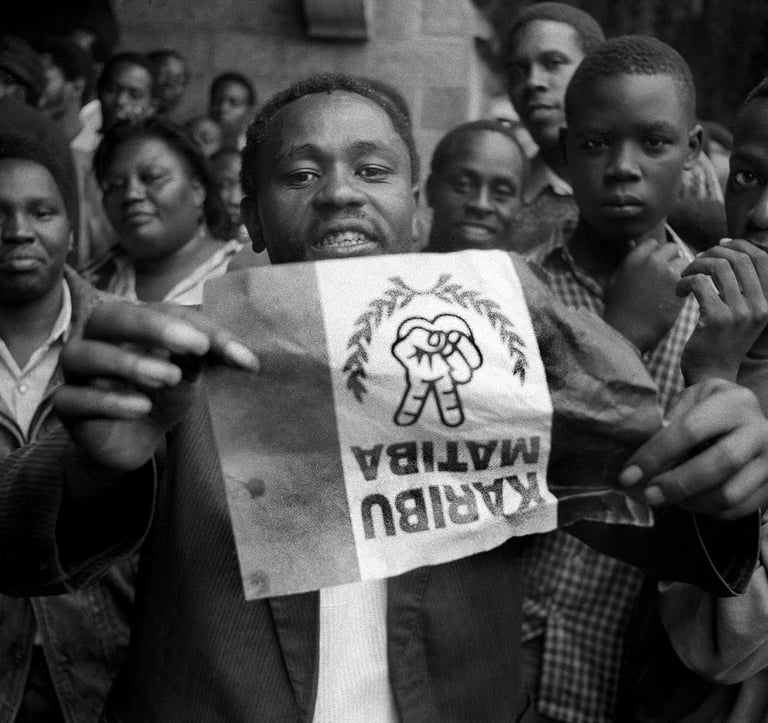

SABASABA

Sabasaba is a nationally recognized commemorative day in Kenya associated with political pluralism, civic rights, and public protest. The word Sabasaba (seventh of July) refers to 7 July, a date that became historically significant due to mass demonstrations demanding democratic reforms. It occupies an important place in Kenya’s political memory and ongoing discourse about governance and civil liberties.

The origins of Sabasaba are linked to the struggle for political openness during a period of restricted political space. On this date, citizens organized large-scale gatherings to call for multiparty democracy, freedom of expression, and constitutional reform. These demonstrations marked a turning point by publicly challenging state control and asserting the right to political participation, known as ushiriki wa kisiasa (political participation).

Sabasaba protests were met with strong state response, including restrictions, arrests, and use of force. Despite this, the events drew national and international attention to demands for reform. The willingness of citizens to mobilize despite risk highlighted growing awareness of haki za raia (civil rights) and the importance of accountable governance. This confrontation shaped subsequent political negotiations and reforms.

Over time, Sabasaba came to symbolize resistance and civic courage. It is remembered not as a single event but as part of a broader reform movement that contributed to changes in political organization and constitutional development. References to Sabasaba often evoke the idea of citizens asserting ownership of the political process rather than passively accepting authority.

Public commemoration of Sabasaba varies. Some years see organized rallies, public discussions, or media reflection on democratic progress. In other years, the date passes quietly but remains present in political language and memory. Activists and civil society organizations may use the occasion to assess the state of demokrasia (democracy) and highlight unresolved issues.

Sabasaba also functions as a reference point in education and political analysis. It is used to illustrate the role of protest in effecting change and the relationship between state power and citizen action. By examining the events of 7 July, learners engage with questions about rights, responsibility, and the limits of authority.

The meaning of Sabasaba has evolved alongside Kenya’s political landscape. While multiparty politics is now established, debates continue around governance quality, electoral integrity, and public accountability. Sabasaba is therefore invoked both as a reminder of past struggle and as a benchmark against which present conditions are measured.

Media coverage plays a role in shaping how Sabasaba is understood. Commentary, interviews, and retrospectives revisit the events and their consequences, reinforcing collective memory. This ongoing discussion contributes to utambuzi wa kihistoria (historical awareness) and sustains public engagement with political history.

In contemporary Kenya, Sabasaba is associated with vigilance rather than nostalgia. It serves as a cautionary reminder that rights were contested and can require defense. The date reinforces the idea that civic space is maintained through active participation rather than granted permanently.

SAMOSA

Samosa is a widely consumed fried pastry snack in Kenya and reflects culinary exchange, urban food culture, and everyday convenience. The word samosa (fried stuffed pastry) refers to a triangular or folded pastry filled with spiced meat, vegetables, or legumes, then deep-fried until crisp. It is popular across social settings and age groups, serving as both a snack and a light meal.

Preparation of samosa involves making or selecting thin pastry wrappers, filling them with a seasoned mixture, and frying them in hot oil. Fillings commonly include minced meat, onions, herbs, and spices, though vegetarian versions are also widespread. The technique of kukaanga kwa mafuta mengi (deep frying) produces a crisp exterior while sealing in moisture and flavor.

Samosa is closely associated with urban life and mobility. It is sold at roadside stalls, markets, school gates, and transport hubs, making it accessible to people on the move. Its portability and quick preparation suit busy schedules, contributing to its popularity among workers, students, and travelers. These qualities embed sambusa within chakula cha haraka (fast food) culture.

Social interaction often accompanies samosa consumption. Friends may share snacks during breaks or informal gatherings, using food as a point of connection. The affordability of sambusa allows spontaneous sharing, reinforcing urafiki wa kijamii (social friendship). Eating together, even briefly, strengthens everyday social ties.

Samosa also plays a role in religious and festive contexts. It is commonly prepared during special occasions and evenings of communal gathering, particularly when families host visitors. Serving samosa demonstrates effort and hospitality without requiring elaborate preparation. Its versatility makes it suitable for both formal and informal settings.

Economically, samosa production supports small-scale entrepreneurship. Vendors require limited equipment and ingredients, enabling low barriers to entry. This activity contributes to biashara ndogo ndogo (micro-enterprises) and provides income for households, especially in urban and peri-urban areas.

Culinary knowledge related to samosa is transmitted informally. Techniques for folding, filling, and frying are learned through practice and observation rather than written recipes. Mastery is judged by texture, flavor balance, and consistency. This hands-on learning supports urithi wa upishi (culinary heritage) even as ingredients and tastes evolve.

Health considerations have become part of contemporary discourse around samosa. While popular, deep-fried snacks are consumed in moderation due to concerns about fat content. Vendors and consumers may adjust portion size or frequency rather than abandon the food entirely. This approach reflects pragmatic adaptation rather than rejection.

Samosa’s widespread acceptance across communities illustrates how foods become integrated through interaction and adaptation. Although its origins lie outside Kenya, the snack has been localized in flavor, availability, and social meaning. It is now considered a familiar and expected part of everyday food landscapes.

WAZEE

Wazee refers to councils of elders who guide community decisions and uphold social order in Kenyan society. The word wazee (elders) describes respected senior members whose authority is grounded in age, experience, and moral standing rather than formal office. Councils of elders function as key institutions for governance, mediation, and cultural continuity at the local level.

Wazee play a central role in decision-making. They deliberate on matters affecting families and communities, such as land use, conflict resolution, and social conduct. Their guidance reflects accumulated knowledge of custom and precedent, supporting uamuzi wa kijamii (community decision-making) that prioritizes consensus over confrontation.

Conflict resolution is a core function of wazee. Disputes between individuals or families are brought before elders for mediation. Through dialogue and negotiation, elders aim to restore harmony rather than assign punishment. This approach embodies usuluhishi wa jadi (traditional mediation), emphasizing reconciliation and long-term stability.

Moral authority underpins the legitimacy of wazee. Elders are expected to demonstrate fairness, restraint, and integrity. Their influence depends on reputation as much as age. When elders act impartially, community trust is strengthened, reinforcing uaminifu wa jamii (community trust).

Wazee also serve as custodians of cultural knowledge. They preserve history, genealogies, and norms through storytelling and instruction. By advising younger generations, elders support urithishaji wa maarifa (knowledge transmission) and continuity of values. Their role links past experience to present practice.

Ceremonial leadership is another responsibility of wazee. They oversee rites of passage, blessings, and public gatherings, lending authority and legitimacy. Presence of elders signals seriousness and adherence to tradition, supporting uongozi wa kiutamaduni (cultural leadership).

Social change has affected the role of wazee. Formal legal systems, education, and urbanization have altered governance structures. Despite this, elders remain influential in many communities, particularly in matters where customary knowledge is relevant. Adaptation allows councils to coexist with modern institutions.

Wazee contribute to social welfare by advising on care for vulnerable members. They encourage collective responsibility and mutual support, reinforcing uwajibikaji wa pamoja (collective responsibility). Their counsel promotes inclusion and respect across age groups.

Public recognition of elders reflects respect for continuity. Elders are often consulted during community planning or commemorative events. Their involvement affirms the value of experience and reinforces legitimacy of collective decisions.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Swahili, we recommend that you download the Complete Swahili Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any other textbook so you can amaze your Kenyan friends and business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get 10 hours of Podcasts to Practice your Swahili listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Swahili today!